How humor helps us learn

LAURIANE RAT-FISCHER •

LAUGHING MATTERS

Article (en anglais) paru dans la revue IAST Connect n°10 (p.6-7)

« A recent arrival from Oxford University, developmental psychologist Lauriane Rat-

Fischer is already at work on a groundbreaking IAST project. With a strong back-

ground in biology and animal cognition, she recently published the first research to show that laughing can facilitate learning in human infants. In Toulouse, she

plans to build on these fi ndings with a series of experiments using eye-tracking equipment, electronic wristbands and other innovative techniques. By investi-

gating the little-known mechanisms involved in children’s social, emotional and cognitive experience of humor, she hopes to change the way we think about

early education and human development. »

Playful laughter is a behavior that humans share with great apes, so it is likely that humor and laughter evolved to serve important functions at both individual and group levels. Recent studies have shown that human infants are surprisingly sophisticated in their use of humor but mystery and controversy still surround questions about

how and why we laugh, especially at an early age. Many authors have suggested that

infants ‘laugh to love’, using humor to forge stronger emotional bonds, but Lauriane’s

research supports the complementary hypothesis that we ‘laugh to learn’.

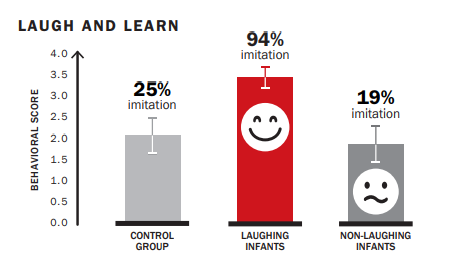

Lauriane’s experiments with infants have centered on a task that requires using a simple rake to retrieve a toy. In a 2012 study, she found that infants spontaneously complete this task towards the end of their second year, but less than a third of 18 month-olds were successful, even after a demonstration

« Humor has been shown to facilitate learning in the classroom,” she says, “through diverse mechanisms such as enhancing attention and motivation, or attenuating stress and anxiety. However, very little is known about how this happens, particularly at a younger age »

To take a trivial example, which of us ever undertakes laborious physical exercise, except to obtain some advantage from it? But who has any right to find fault with a man who chooses to enjoy a pleasure that has no annoying consequences, or one who avoids a pain that produces no resultant pleasure?

ART OF SCIENCE

Lauriane participated in the first Art & Science exhibition at the British Houses of Parliament last year, aimed at raising awareness of the importance of the 1001 first critical days in infancy. “We believe this kind of conversation and partnership between artists, scientists and politicians is an asset,” she says, “inparticular considering

the impact our research could

have on policies related to

infant mental health and early

parental education.”

So is laughter a tool to improve learning, or are people with a sense of humor just better at learning? Lauriane insists that differences in personality cannot account for the improved performance of the infants who laughed: “It is possible that the laughing infants already had a lower threshold for laughing and smiling. Such temperamentally ‘smiley’ babies might be more likely to engage with the environment and therefore to attempt and succeed at the task. These ‘smiley babies’ may also have perceived the experimenter’s smiles and laughs as encouragements. But the experimenter smiled at the object and looked at the infant in both humorous and control groups. And the experimenter who performed the demonstration and smiled at the infants was different from the one who tested them. If only individual differences account for the differences between laughing and non-laughing babies in the humorous group, we would expect half of the control group to also perform better, but this is not the case.”

Another possible explanation is that laughing babies have higher social skills, interacting more easily with others in different social situations. “In our case, laughing infants may have been more comfortable in the presence of strange adults and more disposed to reproduce

others’ actions. It could be that all infants learned in both groups but only those who laughed demonstrated that they learned by reproducing the action.”

Research elsewhere has linked adults’ sense of humor with their socio-emotional capacities. Backed by IAST, Lauriane hopes to replicate such studies on infants to better understand the relations between humor perception, social interactions and learning. She also wants to investigate the possibility that laughing babies have higher cognitive capacities, allowing them to grasp the incongruity, which is known to be a key component of humor perception.

An alternative explanation for Lauriane’s results is that it is positive emotion, rather than humor or laughter, that improves

learning. “Positive emotions in adults have been shown to improve creative problem-solving and facilitate cognitive » exibility,” she explains. “It has been argued that this is because they stimulate endorphin release

and increase brain dopamine levels.” She hopes to investigate whether this effect also

occurs in infants, expanding on research by others which has shown the learning benefits of establishing a social connection with the infant.

To develop her experiments, Lauriane will be assisted by IAST psychology program director Astrid Hopfensitz and the collaborator from the original study, Rana Esseily.

She will be using the state-of-the-art facilities at the Centre d’études toulousain du jeune enfant (Baby Lab Toulouse, supervised by Hélène Cochet).

The project will

focus on the internal and individual mechanisms of enhanced learning, with a series of behavioral experiments involving eye tracking techniques, various physiological responses as well as questionnaires completed by the parents and measuring infants’

socio-cognitive skills.

This exciting research has already had a

significant impact among psychologists and

people working in the educational system.

Lauriane hopes that her efforts to understand the complex psychological processes

of humor and laughter will help establish

appropriate early learning environments,

and improve mental health, education and

well-being for children and adults.